From tropical parasites to stubborn bacteria, swimmers often share the water with more than just other people.

Swimming may be one of humanity’s oldest pastimes — the first known pool dates back to 3000 BCE in the Indus Valley — but along with its benefits come hidden hygiene challenges. Even today, poorly maintained public or private pools can become breeding grounds for infections.

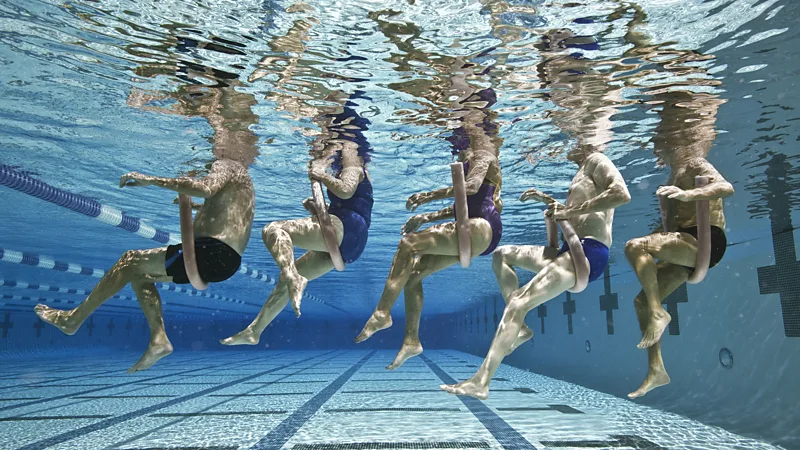

Swimming is widely celebrated for its health perks, offering a full-body workout that’s easy on the joints and great for cardiovascular fitness. But on rare occasions, pools have been linked to outbreaks of stomach and respiratory illnesses. Even in clean pools, chlorine is working harder than most of us realize to keep harmful microbes at bay.

So as swimmers take to the water this summer, it’s worth asking: what might be lurking beneath the surface?

What microbes might be in the water?

In England and Wales, swimming pools have been the top setting for waterborne intestinal disease outbreaks over the past 25 years. The leading culprit? The parasite Cryptosporidium.

This parasite triggers gastrointestinal illness that can last up to two weeks, bringing diarrhoea, stomach cramps, and vomiting — and for about 40% of cases, symptoms return after seeming to subside.

While these illnesses usually clear up in healthy adults, they pose greater risks for young children, older adults, and those with weakened immune systems, explains Dr. Jackie Knee, an assistant professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Cryptosporidium spreads when someone infected has a “faecal accident” in the pool, or when swimmers ingest tiny traces of contaminated matter, Knee says. What’s more, people can continue to shed the parasite even after symptoms stop, adds Ian Young, an associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University.

And despite best efforts, pool water inevitably finds its way into our bodies. A 2017 study in Ohio found that adults swallowed about 21 mL of pool water per hour of swimming, while children took in about 49 mL.

The risk increases in busy pools. A study that sampled six pools weekly during summer 2017 found Cryptosporidium in 20% of the water samples — most often during peak hours.

But parasites aren’t the only concern. Stuart Khan, professor at the University of Sydney, notes that opportunistic bacteria like Staphylococcus can infect the skin, while damp changing rooms can harbor fungi that cause athlete’s foot and other infections.

Swimmer’s ear — caused by water trapped in the outer ear canal — is another common issue, though it isn’t contagious. Rarely, parasites such as Acanthamoeba can infect the eyes, potentially causing vision loss. And inhaling mist containing Legionella bacteria could lead to Legionnaires’ disease, a serious lung infection.

Are these infections common?

Thankfully, major outbreaks from swimming pools remain rare. “We don’t see too many waterborne disease outbreaks in public pools,” says Young. “That suggests chlorine disinfection is working most of the time — but occasionally, lapses happen.”

So while swimming pools generally offer safe recreation, it’s worth staying mindful of hygiene — both personal and poolside — to ensure the water stays as clean as possible.