If you walk into a doughnut shop in California, the chances are it’s owned by a Cambodian family. That’s because of a refugee who built up an empire, and became known as the Donut King, only to lose it all.

Ted Ngoy was a high school student in Phnom Penh when he first set eyes on Suganthini Khoeun, the daughter of a high-ranking government official.

“She was so beautiful,” he remembers. “You can’t find any prettier woman besides her.”

All the boys at his school were in love with her, and as a poor half-Chinese boy from a village near the Thai border he had no chance. “She was powerful, like your royal princess,” says Ted. And she was heavily chaperoned.

But then Ted discovered that the tiny room where he lodged, on the fourth floor of a walk-up apartment block, overlooked Suganthini’s villa. And he saw an opportunity. Every evening, he sat by his open window and played the flute. On hearing the music float across the quiet city, Suganthini’s mother remarked that whoever was playing must be in love.

One night, he saw Suganthini on her balcony, and decided it was time to make his move. He wrote a note, telling her that he lived in the building opposite and was the flute player. He wrapped the note around a stone, and threw it down.

His gesture went unreciprocated for days. But then one of Suganthini’s servants appeared at his door with a reply.

“The note said, ‘I appreciate you blowing the flute. It’s so amazing, so touching.’ And then we started communicating, bringing back and forth the messages,” Ted says.

“What happens if I decide to jump into your room?” Ted wrote one day.

Suganthini replied, “Well be careful, if you don’t jump into my room, you’ll jump into my mum’s room.”

She thought Ted was joking, but he was serious. Despite the villa’s armed security guards and guard dogs, one rainy night Ted climbed up a coconut tree and over the barbed wire and made his way in through a bathroom window.

He took a chance and opened a bedroom door – and there was Suganthini, fast asleep.

He woke her up and she was about to scream for help, when she realised it was her classmate.

“What are you doing here?” she asked.

“Well, it is because I’ve fallen in love with you,” Ted replied.

“But what shall we do in the morning? I have to go to school.”

“Don’t worry, I will hide under your bed,” said Ted. And that’s what he did.

Suganthini smuggled him food at night, and after many days she said she loved him too. They made a blood pact, promising to be forever faithful. He says he hid in her room for 45 days until he was discovered.

Suganthini’s family insisted Ted break it off by telling her he didn’t love her. He did as he was told, but then pulled out a knife and stabbed himself, declaring he would rather die than live without her. While he was recovering in hospital, Suganthini also made an attempt on her life. Faced with such determination, her family allowed the young lovers to be together.

“It’s a crazy story, but it’s true,” says Ted, now 78. “I had true love for her.”

But he admits he was also aware that conquering Suganthini’s heart held out the promise of a better life.

They married and started a family, and life was good until civil war broke out in 1970, between the government and the communist Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot.

Ted, who spoke four languages, was offered a post as liaison officer in Thailand by Suganthini’s brother-in-law, Gen Sak Sutsakhan. Instantly acquiring the rank of Major, Ted and his young family moved to Bangkok, and every month he travelled back to Cambodia to collect the wages for his soldiers.

But the situation at home was increasingly dangerous and on his last trip, in April 1975, the capital fell. Ted managed to escape on the last flight out of Phnom Penh but Suganthini’s parents were left behind. She later discovered that they were among the first to be executed by the Khmer Rouge.

The following month, US President Gerald Ford insisted the US should welcome 130,000 refugees from Vietnam and Cambodia, telling any critics: “We’re a country built by immigrants from all areas of the world, and we’ve always been a very humanitarian nation.”

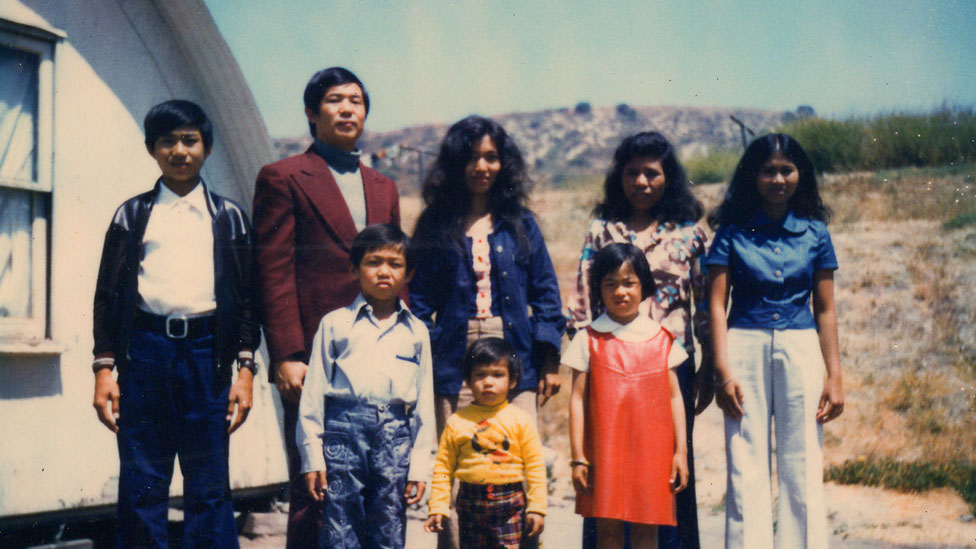

Ted and Suganthini sold everything they had and arrived in California on one of the first refugee flights, with their three children, an adopted nephew and two nieces. The family were housed in a hastily erected refugee camp on a marine training base, Camp Pendleton. In order to be allowed to leave the camp and find work, they needed an American sponsor, who would find them a job and somewhere to live.

For weeks, they watched other families leave, until finally they, too, were sponsored by a pastor from a church in Tustin, Orange County, about 35 miles south of Los Angeles. Ted worked as the church janitor but he soon realised earning $500 a month wouldn’t be enough to support his family. With the pastor’s permission he went out and got two more jobs, as a sales person from 6pm to 10pm and petrol attendant from 10pm to 6am.

Next to the petrol station there was a doughnut shop called DK Donuts. It smelled delicious and when he first tasted one it reminded him of something from home – a fried pastry, also circular, called nom kong. “It made me homesick,” says Ted.

All night long Ted would watch people buying coffee and doughnuts, and he realised it was a good business. One night he asked the woman at the counter if saving $3,000 would be enough to buy a doughnut shop. She said he would be throwing his money away. Instead, she told him about a training programme run by the doughnut chain, Winchell’s. Ted became their first South East Asian trainee.

“I learned to bake, to take care of payroll, cleaning, sales – everything,” he says. One of the tricks he learned was to bake doughnuts in small batches throughout the day to keep them fresh – and because the smell of baking was the best form of advertising.

When he completed his three-month training, Winchell’s gave him a shop to run on Balboa Pier, a tourist spot on the Newport peninsula not far from Tustin. Suganthini became the smiling face behind the counter, even though she hardly spoke any English. Ted did a lot of the baking at night, with his youngest son, Chris, collecting a light dusting of flour as he slept beside him in the kitchen.